The Car the World Forgot

Posted by AV Flox on Aug 7th 2013

Growing up, Ed Howard was an avid fan of the vaudeville comedians Abbott and Costello. Like any fan, he spent time poring over any media relating to his idols that he could get his hands on. One of his favorite photos was one of Lou Costello up against a car that even his brothers, who practically lived in the garage working on cars, couldn’t identify. What was this mysterious all steel hybrid of a business coupe, club coupe and convertible?

It would be years before Howard would get his answer. As an adult, idly paging through the Encyclopedia of Motor Cars, he chanced upon the car that had once cruised across his boyhood dreams: it was a 1948 Playboy, a car briefly produced by the Playboy Motor Car Corporation that everyone forgot after the company went bankrupt in 1951.

The year the Playboy car hit the streets was revolutionary – the clouds of war were beginning to clear and the freedom so many had fought for was leaving the realm of abstraction and showing real-world implications. In 1946, the United States Supreme Court ruled in Hannegan v. Esquire, Inc. that the Postmaster General didn’t have the power to prescribe literary or artistic standards for non-obscene publications sent through the mail, a triumph against the oppressive Comstock laws that controlled everything Americans looked at and read.

That same year, Howard Hughes’ western The Ourlaw was finally released widely, after a multi-year battle with everyone from the Hollywood Production Code Administration to Century Fox. In the end, it was the very protests of vocal anti-obscenity groups that mobilized the public in the film’s favor, leading it to become a box office hit in 1946 and catapulting Jane Russell to sex icon status.

The war effort had catalyzed the development of many useful drugs, among them penicillin. The year 1942 had seen the first patient treated with U.S.-made penicillin and major advances in the following years allowed the United States to begin producing the antibiotic in greater quantities, making the once scarce drug more accessible to the public. By 1946, penicillin’s ability to treat syphilis and other sexually transmitted illness was well known, liberating a hesitant public to pursue its pleasures.

And 1946 was also the year that a 20-year-old on the G.I. Bill was enrolled at the University of Illinois after his discharge from the U.S. Army. His name was Hugh Hefner.

No one at Playboy Motor Cars in Buffalo, New York, had any way of knowing the part they would play in the history of this country. Theirs would be the car everyone forgot and the name that lived forever.

Hugh Hefner never drove a Playboy car nor did he, in the late 40s, have any illusions that he might one day change the world. After graduation, he found that the job market was saturated with veterans looking for work. None of the positions available interested him. Hefner floated from one job to the next, all the while drawing cartoons no newspaper seemed eager to run. To save money, he and his wife had moved in with his parents, a situation that had taken whatever spark remained between them out of their marriage.

Finally, he found himself a gig with George Van Rosen, a businessman who had identified in the appeal of the pinup girl the desire for images of scantily-clad women. In 1951, Van Rosen would launch Modern Man, the most successful of his “girlie” magazines. Though Hefner was already working for him, even this endeavor didn’t inspire him. Van Rosen, ultimately, was a businessman and he ran his magazines as a business. His passion was for profit, not for creating a platform to breathe life into a new lifestyle. Hefner was passionate about the freedom of sexual expression – he found Van Rosen’s offices sterile and devoid of the wonder and sensuality that decorated the pages of Modern Man.

Though he had finally managed to move out of his parents’ house by 1953, when he reflected on his life, Hefner felt every bit a failure. He had conformed to society’s expectations: he’d served his country in the military, he had gone to college, he had married and had a child, but at 27, all he had to show for himself was a passionless marriage and a 12-year-old Chevy.

He’d had enough. With a $600 loan, he decided to launch his own magazine. The money was quickly put to use. An avid reader of Advertising Age – a magazine that has been covering marketing, advertising and media since its inception as a Chicago broadsheet in 1930 – Hefner saw that a local calendar manufacturer owned pictures of Marilyn Monroe, taken before she had made it as a star. Hefner drove over immediately and dropped $500 on one of the photos, which depicted Monroe stretched out on a lush red backdrop, with nothing on “but the radio.” This turned out to be a shrewd move. As his vision solidified, Hefner managed to pick up $2,000 more from an old buddy, Eldon Sellers, who would go on to become the magazine’s business manager.

Hefner had intended to name the magazine Stag Party, but the publisher of the 25-cent, men’s adventure magazine Stag had threatened a trademark infringement lawsuit, leaving Hefner in a tight spot. Sellers suggested that Hefner name his magazine Playboy, remembering his mother had once worked for a car company of that name. As Gay Talese, who chronicled Hefner’s journey in the classic Thy Neighbir’s Wife, wrote, Hefner was obsessed with F. Scott Fitzgerald and the glamour of the 1920s and immediately took to the name.

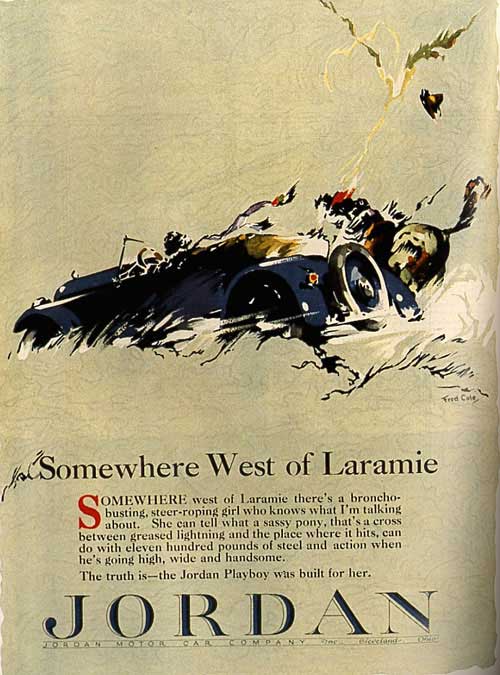

Of course, the Playboy car that Sellers was referring to had been manufactured in 1946, not the Roaring Twenties. It’s likely that Hefner, who had for years read Advertising Age and was fascinated by the world of media, was thinking of the Jordan Motor Car Company’s car of the same name, which changed the world of advertising forever in 1923 with an ad called “Somewhere West of Laramie.”

The story goes that a car maker by the name of Edward S. Jordan was riding west on the Union Pacific Railroad from Ohio when he looked out the window and saw an attractive woman on a horse, racing the locomotive. The image of this woman, so free against the setting sun overwhelmed him. He turned to his companion and asked where they were, “Somewhere west of Laramie,” came the answer.

Unlike nearly all ads of the time, which gave details about their products, Jordan drafted ad copy meant to convey that same wonder he had experienced while looking out the window at that beautiful woman racing alongside his train.

“Somewhere west of Laramie there's a bronco-busting, steer roping girl who knows what I’m talking about,” the ad, which ran in the then-weekly Saturday Evening Post magazine, read. “She can tell what a sassy pony, that’s a cross between greased lighting and the place where it hits, can do with eleven hundred pounds of steel and action when he's going high, wide and handsome. The truth is – the Playboy was built for her. Built for the lass whose face is brown with the sun when the day is done of revel and romp and race. She loves the cross of the wild and the tame. There's a savor of links about that car – of laughter and lilt and light – a hint of old loves – and saddle and quirt. It’s a brawny thing – yet a graceful thing for the sweep o' the Avenue. Step into the Playboy when the hour grows dull with things gone dead and stale. Then start for the land of real living with the spirit of the lass who rides, lean and rangy, into the red horizon of a Wyoming twilight.”

The ad featured an image depicting a flapper in a Jordan Playboy, racing another woman on horseback in a dynamic spread across the ad. Advertising Age ranks the ad at number 30 among the top 100 advertising campaigns of the century. Indeed, the Jordan went down in history for its advertising campaigns.

It could be said that the Jordan Motor Car Company was the Apple of cars – assembling beautifully-designed high-end machines out of components furnished by other companies. Jordan knew what men and women of the age wanted: smart-looking cars for discerning, smart-looking people. His cars were styled to perfection, and came in a variety of colors. At a time the Ford Model T was only offered in black, Jordan’s cars came in a dizzying array of different shades of red, blue, green and gray.

It’s not unlikely that these were the cars that Hefner was thinking about when he perked up on hearing the name Playboy. You know the rest of the story: Playboy was founded on Hefner’s kitchen table in his Hyde Park apartment in 1953 and rose to prominence immediately, with a monthly circulation skyrocketing from 60,000 to 400,000 within two years.

Playboy magazine would change the way we looked at sexually suggestive images by framing them with literature and thoughtful articles, effectively taking sex out of the realm of the tawdry and allowing our desires to live alongside our intellect. Hefner would back many people fighting oppressive laws over the years, never budging from the belief that we should enjoy the freedom to express ourselves sexually as we see fit.

Today, the Playboy brand and its famous rabbit logo are recognized worldwide. It’s possible that the magazine would have reached equal renown regardless of its name, but there is something to be said for the power of a name. Words are evocative and Stag simply doesn’t conjure the same images that Playboy does.

All because of a little car that everyone forgot.

Well, everyone except Ed Howard. Having at long last identified the car he’d seen as a child, he joked to his brothers, “well, now I need to own one!” What started as an off-handed comment over beers soon took possession of his imagination.

Twelve years ago, his search led Howard to a man who had not one, but two Playboys – one had been restored and the second was still in need of work. He was selling the second. Howard didn’t hesitate; he immediately booked a flight from California to North Carolina to meet with him.

“It had been painted, the upholstery looked good,” Howard recalled when we spoke on the phone. “But it was missing a lot of chrome pieces – it didn’t have bumpers, it didn’t have the hood ornament or other trim pieces. Obviously you can’t go to Pep Boys and buy chrome for this car so I made it a treasure hunt.”

Slowly, a search that had started somewhat idly became a full-time quest. After some more detective work, Howard was able to track down the grandson of the founder of the Playboy Motor Car Corporation.

“He still lives in Buffalo, New York,” Howard told me. “He’s a pharmacist. He still had the mold for the bumpers in his old family barn. I mean, they just never threw anything away. So we sent those molds down to a metal smith in Pennsylvania and that’s how I got the bumpers.”

The scavenger hunt would lead Howard all over the place. Eventually he located a former employee of the company, a 79-year-old who was so inspired by Howard’s desire to restore this car that he carved Howard a new hood ornament. Other restoration work involved rebuilding the radiator, carburetor, and furnishing new tires. Finally, the car was complete. Howard got it licensed and, in 2006, loaned it to the Petersen Automotive Museum in Los Angeles.

In 2008, while watching television, Howard learned that Hugh Hefner had gotten the name for his magazine from the car.

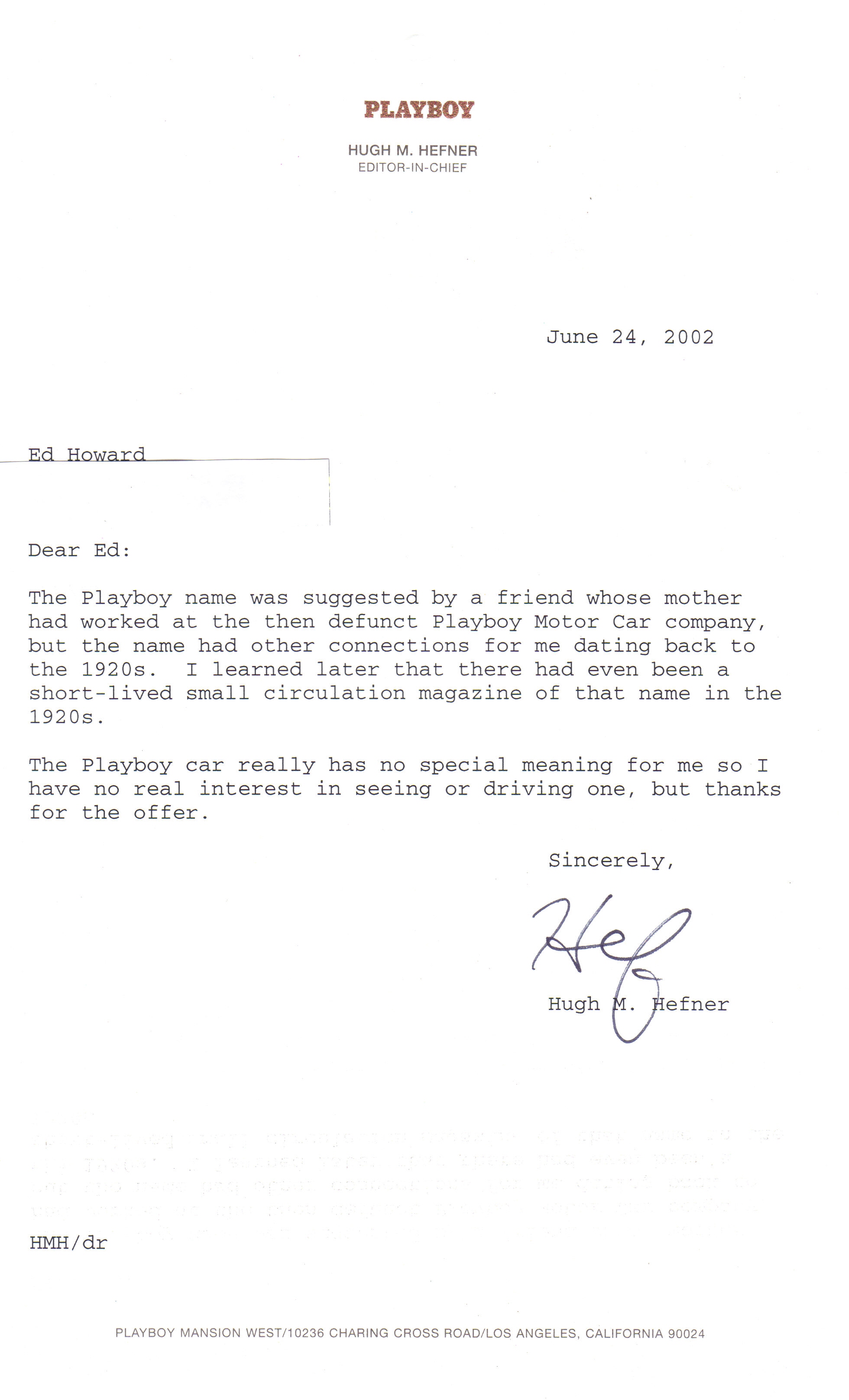

“I didn’t believe it,” he said. “So I tracked down the address of the Playboy Mansion out in Los Angeles and – what the heck? I wrote Hugh Hefner a letter that said ‘I’m the only person on the entire West Coast who has a Playboy car, is this a true story?’”

Howard offered to take the car up to Holmby Hills for the infamous editor-in-chief to take a ride. On June 24, 2008, less than two weeks after sending the letter, Howard received a response:

Dear Ed:The Playboy name was suggested by a friend whose mother had worked at the defunct Playboy Motor Car company, but the name had other connections for me dating back to the 1920s. I learned later that there had even been a short-lived small circulation magazine of that name in the 1920s.

The Playboy car really has no special meaning for me so I have no real interest in seeing or driving one, but thanks for the offer.

Sincerely,

Hugh M. Hefner

The letter seems to suggest that we may not be wrong in thinking that when Sellers had mentioned the name Playboy to Hefner, the fledgling publisher had imagined the striking visuals created by Edward S. Jordan’s in his 1923 campaign for the other Playboy car.

As for the car that the world forgot? It’s believed that the company produced 97 cars before closing its doors. Today, 47 Playboys by the Playboy Motor Car Corporation have been identified and Howard estimates that only 20 of these are road-worthy.

He was hesitant to tell me how much he thinks his Playboy is worth.

“We jokingly call the Playboy the ‘poor man’s Tucker,’” Howard said with a laugh, referring to the Tucker 48, which was briefly produced in Chicago in 1948 by the Tucker Car Company. Only 51 of these cars were manufactured before the company folded in the midst of a stock fraud scandal – a story that would become legend thanks in part to Francis Ford Coppola’s 1988 film, Tucker: The Man and His Dream.

Last year, a Tucker 48 sold at auction for $2.6 million – $2.9 million when you take into account buyer’s fees.

“I don’t think the Playboy has as much of a famous story as the Tucker does,” reflected Howard. “So what is the car worth? I’m just not willing to give you a number because I just don’t know.”

He and other Playboy owners are working to remind the world of the little convertible that, despite itself, changed everything.